Historical sources provide information to approximate the color of Mesoamerican dogs. It is reasonable to propose that the xoloitzcuintle (with hair and without hair) as a population subset could share, in large part or in its entirety, the chromatic palette of the rest of the dogs in the region. The prehispanic iconography shows that the dogs were represented in the codices showing a range of colors that includes white, red, yellow, black and especially the white dog with black spots. In fact, it has been said that for symbolic purposes, the dog was the spotted animal par excellence, both in the Altiplano and in the Maya area. Among the Mayans, the sign "Oc" (dog) simply consists of an outline of ears and a stain. Such spots in some cases have celestial meanings (Seler, 2008: 40-63):

"Due to its practical, ritual and mythological importance, in the manuscripts we often find the dog represented. In Mexican codices the dog is usually painted white with large black spots. It also appears only in white ... also only in black. In most cases a large black spot is present in the area around the eye. [Other times the figures] are in yellow or vermilion [or] completely red ... In the Nutall codex the black spot on the eye sometimes has circular white spots on the black background. In this case it is the cicitlallo, or painting of the starry sky, the symbol of the starry sky or the night. "(Seler, 2008: 42)

The first European references about American dogs are simple mentions about the Caribbean dogs. These dogs were transferred to the islands from the continent and hence their representativeness.

On the second voyage of Columbus, Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca, a Sevillian, embarked at the end of 1493 or the beginning of 1494 wrote from La Española a letter-relation addressed to the Cabildo de Sevilla. From this author we know the following passage regarding the arrival in Haiti after having explored other islands including Puerto Rico:

"It is a very singular land, where there are infinite large rivers and large mountains and large flat valleys, great mountains; I suspect the herbs never dry all year round. I do not think that there is any winter in this one in the other because for Christmas many bird nests are missed, with birds and eggs with them. In it or in the others, we have never seen a four-foot animal, except for some dogs of all colors, as in our homeland, making it like large gosques; of wild animals, there is no ... "(Álvarez Chanca, 1973: 51)

This testimony has great relevance because it is possibly the first note on the color of American dogs, at a time when any influence of dogs introduced from Europe is still negligible. Although it does not contain an explicit list, a chromatic diversity comparable to that of the Old World is evident. The above supports the premise that several, if not all, the colors of the dog's coat were present in America from very remote times.

Later, in the book titled "First Trip of Philip the Handsome to Spain in 1501", published for the first time in 1876 (Zalama, 2006), Antonio de Lalaing, relates that he was taught as curiosities of the West Indies, to Juana de Castilla and Felipe I, the Beautiful:

"... two very new things, the one was a completely black dog that did not have any hair and lengthened its snout according to the shape of a black one; the other a green parrot ... "(Lalaing, 1952, in Weiss, 1970).

As is widely known, the third voyage of Columbus (1498-1500) also included contact with the coasts of northern South America (Venezuela). It would not be until the fourth trip (1502-1503) that would touch the Caribbean coast of Central America, but never the coasts of Mexico According to the dates considered, this first black dog and bald in Europe had to arrive in Spain from either the Antilles or South America.

Years later, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún in his work entitled General History of Things of New Spain (1547-1577), in the Eleventh Book entitled "Of the properties of animals, birds, fish, trees, herbs, flowers, metals and stones, and colors "relates:

The dogs of this land have four names: call chichi, itzcuintli, xochiocóyotl and tetlamin and also teúitzotl. They are of different colors, there are some blacks, others white, other ashen, other buros, other dark brown, other brown, other brown and other stained. (Sahagun, 1992: 628)

Again insists on coats of different colors in the entire range possible from black to white, including spotted dogs. In addition the illustrations show diverse dogs including one interpreted like "golondrino" (Blank, 2006).

Next, in the Appendix of the Third Book, Sahagun recounts the myth of the crossing of the river in the Underworld and again some fur colors are mentioned, since contrary to the popular version, dogs with hair are involved in this passage:

23.- For this reason the natives used to have and raise puppies, for this purpose; and more they said, that dogs with black and white hair could not swim and cross the river, because so-called white-haired dog said: I washed myself; and the black-haired dog said: I've been stained a dark color, and that's why I can not pass you by. Only the red-haired dog could well carry the deceased on their backs, and so in this place of hell called Chiconaumictlan, the deceased were finished and dead. (Sahagun, 1992: 206-207)

On the other hand, Francisco Hernández de Toledo in his capacity of "protomédico general of our Indies, islands and the mainland of the Ocean Sea" disembarked in Veracruz in 1571 and carried out field work until 1574, in order to study the native flora and its medicinal uses, as well as fauna. In his Natural History of New Spain the theme of dogs is touched and he mentions color for canine forms:

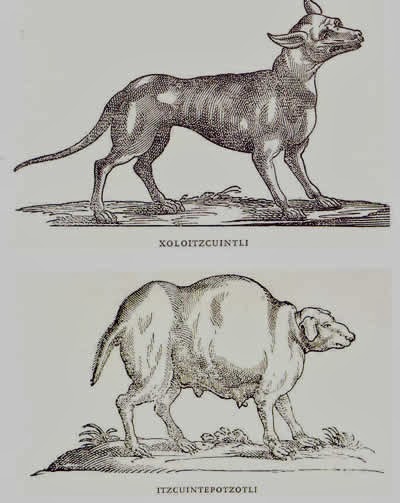

"... The first one, called Xoloitzcuintli, surpasses the others in size, which is usually more than three cubits, and has the peculiarity of not being covered in hair, but of a smooth and smooth skin stained with fawn and blue. The second one is similar to the Maltese dogs, stained white, black and tawny, but gibbous, with a certain curious and funny deformity, and with the head as if coming out of the shoulders; they usually call him Mechacanese in the region where he was born. "(Hernández, 1999: 152-153)

Therefore, the text refers to the naked dogs stained in two colors and a dog with three colors in its fur is clearly described. Already in the 18th century and based on Hernández, the Jesuit Francisco Saverio Clavigero (Clavigero, 1826: 33-43) exhibits a series of four-legged animals among which the Joloitzcuintli and other "tricolor" dogs are mentioned:

"... The first [itzcuintepotzotli], whose name means, hunchbacked dog, was the size of a Maltese dog, and his skin was spotted with white, tawny and black. The head was small, with respect to the body, and seemed intimately attached to it, for being the thick, short neck. He had a soft look, low ears, a nose with a considerable prominence in the middle, and a tail so small that it barely reached the middle of his leg: but the most singular thing about him was a hump that caught him from the neck to the back room . The country in which this quadruped was most abundant was the kingdom of Michuacan, where it was now called ... The Joloitzcuintli, is greater than the two preceding, because in some individuals the body is more than four feet long. It has the right ears, the thick neck, and the long tail. The most singular thing of this animal is to be entirely deprived of hair; because it only has on the snout some long, twisted bristles. His whole body is covered with a smooth, soft skin, the color of ash, but stained in part black and tawny ... "(Clavigero, 1826: 40-41)

Also during the 18th century, in his famous work Systema Naturae Carlos Linneo laid the foundations for a modern scientific taxonomy using the binomial system. In the twelfth edition of this work, the description of the Canis mexicanus that includes the term Xoloitzcuintli is included and in Latin this "species" is described as: "Corpus cinereum fascis fuscis. Maculae fulvae in fronte collo, pectore, ventre, cauda ", that is to say with: Body gray brown, compact. Yellow spots on the forehead, neck, chest, belly and tail. (Linné, 1776: 56-60). It is worth mentioning that this name is now obsolete and the xoloitzcuintle is currently classified as another race within the species Canis lupus familiaris, that is, the domestic dog.

In conclusion, it is possible to affirm that Mesoamerican dogs have historically presented a very wide range of colors that includes solid colors as well as stains in two and up to three colors, both in fur and skin. Stained dogs, in addition to having been represented and mentioned at different times, have cultural significance, especially due to the emphasis recorded in the codices. The same can be said of the black, red and white dogs mentioned in the myths, since these colors are related to the directions in the ancient worldview. Although from the sixteenth century Mesoamerican canine populations have been genetically enriched with contributions from other continents, chromatic diversity is inherent to them and it is not necessary to resort to such external sources to explain their genetic variability.

Escribir comentario